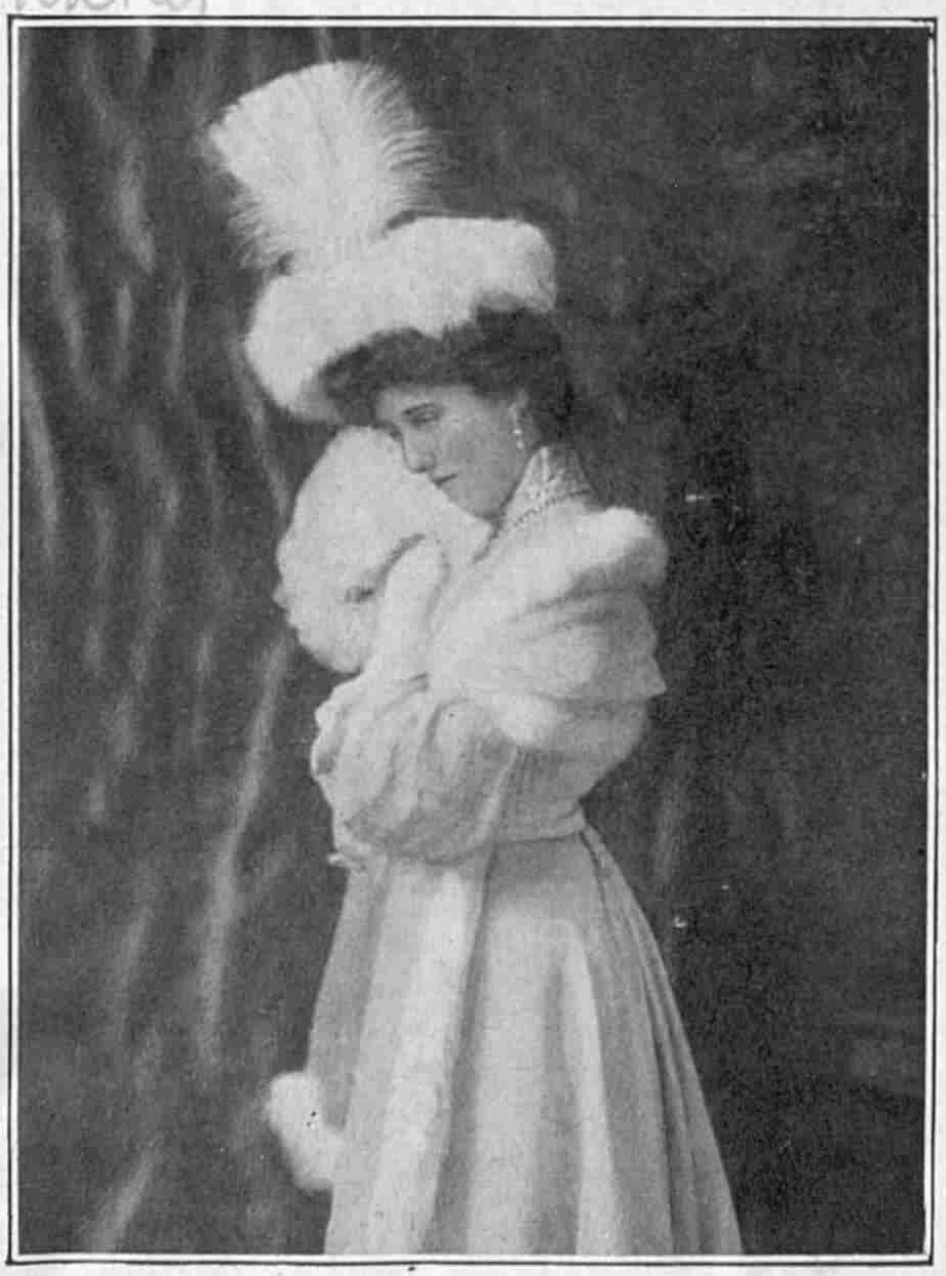

Isabella Grenander. Image copyright the British Library Board. courtesy of the British Newspaper Archive. Henning Grenander is one of the big names in the early days of figure skating. He was born in 1974 in Sweden and won worlds in 1898, when it was held in London. In the same year, according to Hines, he… Continue reading Mrs. Grenander

Category: Skaters

The Waldrons again

Since my last post on them, I've been tracking Mr. W. A. V. Waldron and Miss B. Waldron through Ancestry.com. Here's some of what I've been able to piece together. William Arthur Vaughan Waldron was born in 1876 in Kent and died in 1933 in Penzance. Tracking this name through the census records revealed the… Continue reading The Waldrons again

Johan Ekeblad

Johan Ekeblad. Courtesyof Wikimedia Commons. Johan Ekeblad (1629--1697) was a prolific Swedish letter-writer who spent a lot of time on the Continent. According to the Swedish Academy, publisher of a great dictionary that's rather like the Swedish version of the OED, he was the first to use the word skridsko in Swedish. This word is… Continue reading Johan Ekeblad

Henry Eugene Vandervell

Henry Eugene Vandervell (1824-1908) is well-known in skating circles as the "father of English style skating." He's remembered for inventing the counter, writing (with T. Maxwell Witham) A System of Figure Skating, and chairing the Ice Figure Committee of the National Skating Association (Hines, 233). But the skating books say little about his personal life.… Continue reading Henry Eugene Vandervell