I previously wrote about what cross-grinding is and why it's not always bad. Here is a photo of one of my skates showing the distinctive marks left by cross-grinding. Cross-grinding leaves many small lines perpendicular to the length of the blade. If the cross-grinding wheel is too coarse (like the one I used with my… Continue reading Cross-grinding example

Category: Metal skates

The Ferodowill skate holder

On January 23, 1917, Joseph Henry Ferodowill of St. Paul, MN, was granted a patent for his skate holder. It's basically two C clamps on a metal base, with some screws that make it adjustable. Popular Mechanics Magazine, vol. 48, no. 4 (October, 1927), p. 160. The advertisement says it's good for "Lengthwise and Cross"… Continue reading The Ferodowill skate holder

The Berghman Skate Sharpener

The Berghman Skate Sharpener This little handheld sharpening device was patented in 1920 by George H. Berghman of Chicago, IL. You squeeze the handles together at the top to open it. When you release the pressure, it clamps onto the sides of the blade. Then you slide it back and forth and the grinding stone… Continue reading The Berghman Skate Sharpener

Combination grind

Back in the days when all serious skaters did both figures and freestyle, everyone had two pairs of skates, one for figures (called "patch skates") and one for freestyle. But having two pairs wasn't a requirement to begin skating. Everyone started out with only one pair. A second pair wasn't considered necessary until second test… Continue reading Combination grind

IJlst, city of skate-makers

IJlst, stad van schaatsenmakers by Edsko Hekman. IJlst: Visser, 2002. Today's book report is on IJlst, stad van schaatsenmakers by Edsko Hekman. IJlst is a a city in Friesland where lots of skates were made in the nineteenth century. This short book (only 64 pages long) is about the 24 IJlst skate-makers. Several of these… Continue reading IJlst, city of skate-makers

Why cross-grinding is (not always) bad

Cross-grinding refers to sharpening skates with a grinding stone whose axis of rotation is parallel to the skate blade. This means that if you hold the skate sideways (blade parallel to the floor), the grinding wheel rotates down. This is how the ordinary bench grinders from the hardware store are set up. A bench grinder.… Continue reading Why cross-grinding is (not always) bad

Robert Jones’s skates again

My Robert Jones skates. In A Treatise on Skating—the first book on skating, published exactly 250 years ago—Robert Jones describes, in great detail, his ideal skates. I made a pair and tried them out. Jones's skates are the type used in England at his time, in contrast to the Dutch type. They have short, curved… Continue reading Robert Jones’s skates again

My new snavelschaatsen

Yesterday I put the finishing touches on my snavelschaatsen. I started them back around the end of February or the beginning of March, so it took me about 9 months to make them, start to finish. My finished snavelschaatsen. These skates are based on a couple of Hieronymus Bosch paintings and some archaeological finds. The… Continue reading My new snavelschaatsen

Fluted skates

Early skating authors had a lot of bad things to say about deep hollows on ice skates. I have said nothing of those skates whose surfaces are grooved, and are commonly called fluted skates, because I think their construction is so bad, that they are not fit to be used; in fact, they are so… Continue reading Fluted skates

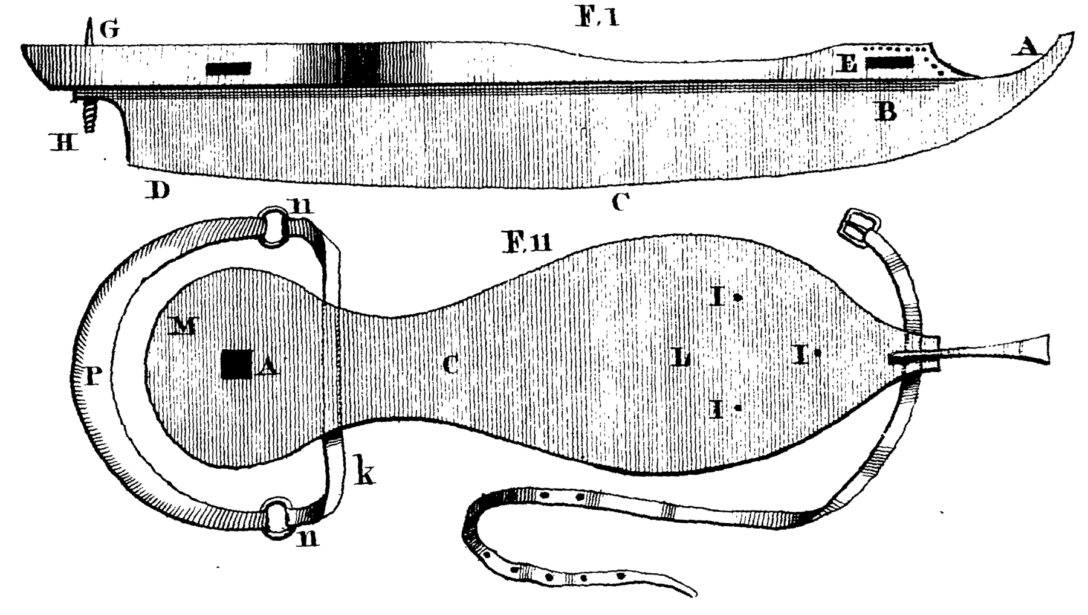

Robert Jones’s skates

In his 1772 Treatise on Skating, Robert Jones describes what he considers the ideal skate in detail, including measurements: Figure 1 (top) represents a skate, made after the English fashion, with some improvements; the proportions are as follows: Let the distance from the point of the fender, A, to the toe hook, which is shewn… Continue reading Robert Jones’s skates