The internet is now full of news about the bone skates that were recently excavated at the two sites on the Taman Peninsula: 39 at Yastrebovskoye-Berezhnoe 1 and four at Armaturny Zavod 1. Most are made from horse metapodia, but a few are from cow metapodia. They are unmodified except for flattening of the grinding… Continue reading Bone skates from the Taman Peninsula

Category: Bone skates

Bone skates in De Proefkeuken

De Proefkeuken is a Dutch children's show about science. In one episode, the two protagonists, Willem and Pieter, make their own skates. One of their homemade bone skates. They go to the Schaatsmuseum Hindelopen and see bone skates at about 6:20. Then they go back to their lab and create their own bone skates. They… Continue reading Bone skates in De Proefkeuken

The new bone skate from Přerov

In the second half of March, Google sent me a bunch of news articles about a bone skate found in Přerov, a city in the Czech Republic. This post is a summary meant to track the evolution of the story. There are of course many more articles and blog posts about this skate. I doubt… Continue reading The new bone skate from Přerov

Internet articles about the Xinjiang skates

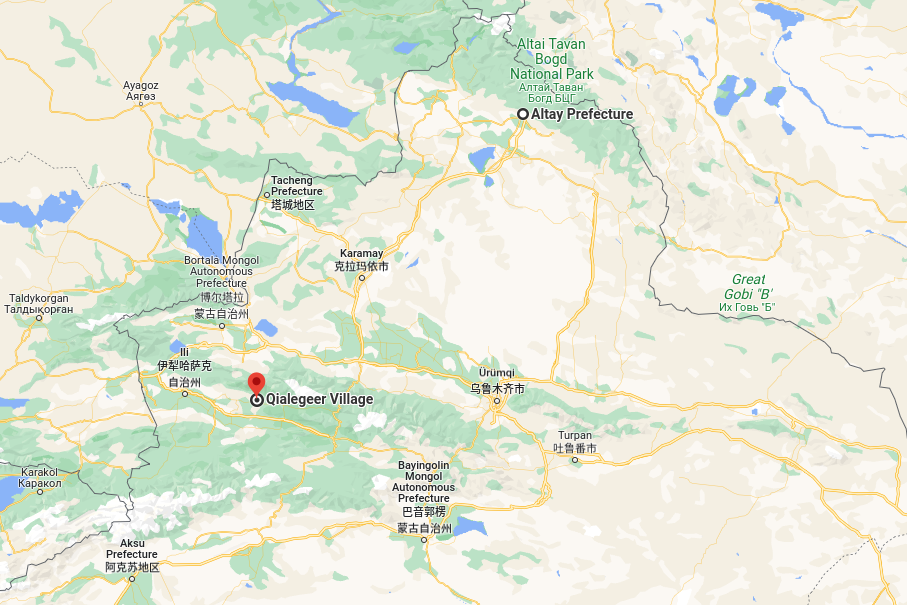

This is just a list of links with some comments. It's an interesting example of how a story spreads and grows despite a lack of reliable new information. Here's the press release from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences by Zhou Ye (2/27/2023, in Chinese). It focuses on the non-skate finds and has roughly the… Continue reading Internet articles about the Xinjiang skates

Ice skating was not invented in Finland

Internet, stop saying it was. The idea that ice skates made from animal bones first appeared in Finland is based on a paper published in 2008 in the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. The authors, two biomechanics researchers from Manchester Metropolitan University, measured the metabolic cost of skating as compared with walking, then ran… Continue reading Ice skating was not invented in Finland

Old bone skates found in China

This last week, the news has been full of reports on the recent announcement (in Chinese) that bone skates have been found in the Xinjiang area. The skates were reportedly found at a tomb in the Gaotai Ruins, which are part of the Jiren Taigoukou Ruins in Qialege'e, a village in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous… Continue reading Old bone skates found in China

Bone skates in Fríssbók

Fríssbók or Codex Frisianus is an Icelandic manuscript written in the first quarter of the fourteenth century. It includes a copy of Magnússona saga (called Saga Sigurðar, Eysteins ok Ólafs in C. R. Unger's edition). The whole manuscript has been digitized and is available at handrit.is! Here is the part about skating, with the phrase… Continue reading Bone skates in Fríssbók

Bone skates in the Guildhall Museum

The Catalogue of the Collection of London Antiquities in the Guildhall Museum lists 16 bone skates. The first, #134, is "said to have been found with two Roman sandals" at London Wall. A few of these skates, including #134, were drawn by Charles H. Whymper; his drawing is preserved in the British Museum. "Five skates… Continue reading Bone skates in the Guildhall Museum

The bone skates from Novgorod

I've finally gotten hold of Oleg Oleynikov's paper on the bone skates from medieval Novgorod. It came out last year, but only recently appeared in the online archive of Russian Archaeology (2021, issue 4, pages 102–118). It's in Russian, and I don't know Russian, so I have been looking at the pictures and references and… Continue reading The bone skates from Novgorod

Bone skates vs. archetype skates

This short video illustrates the major advantage of metal-bladed skates over bone skates. Even if the earliest metal-bladed skates were used with poles (I'm not sure when people started pushing with their feet), it was much easier to turn on them. Here I'm trying to keep the hockey circle between my feet on my archetype… Continue reading Bone skates vs. archetype skates