Lincoln Castle Revealed from Oxbow Oxbow's new book about Lincoln Castle, Lincoln Castle Revealed: The Story of a Norman Powerhouse and its Anglo-Saxon Precursor describes two bone skate fragments found during the excavation. The authors date them to before the Norman Conquest and include them in the catalog of artifacts under "Recreation"—where they are the… Continue reading The bone skates from Lincoln Castle

Category: Bone skates

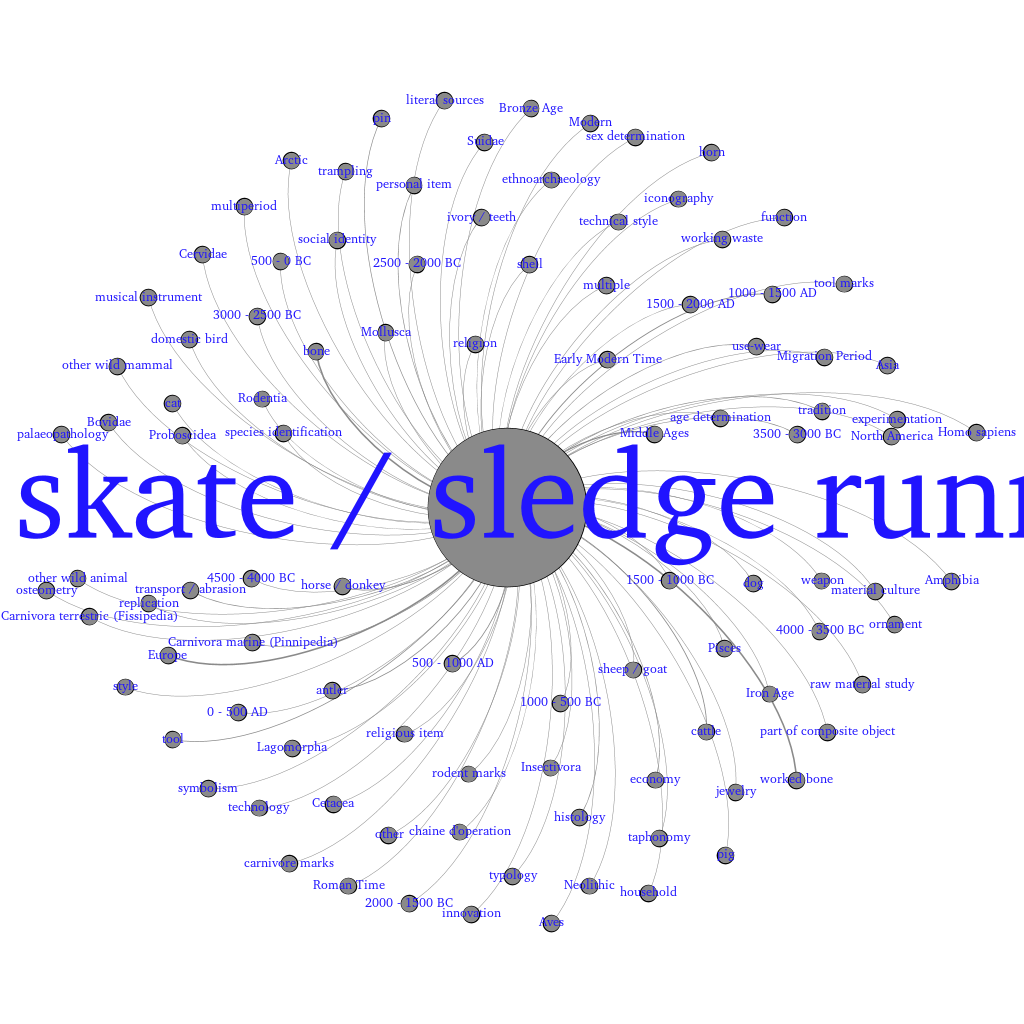

Bone skates and keywords

I used Gephi to make a graph of all the keywords connected to bone skates in the WBRG reference database. Graph generated using Gephi. Most of the results aren't very surprising. Of course bone skates are strongly linked to worked bone, bone, Europe, and the Middle Ages (1000–1500). More surprising are the links to North… Continue reading Bone skates and keywords

Arthur MacGregor

Arthur MacGregor is one of the heroes of bone skates studies. He proved that bone skates really were skates in 1975 by making a couple of pairs and skating on them. The next year, he published a really great review article. His dissertation Skeletal Materials presented the bigger picture. And then his book Bone, Antler,… Continue reading Arthur MacGregor

Did Swedish immigrants to the Midwest use bone skates?

Two facts are clear: People were still using bone skates in Sweden in the nineteenth century (see pp. 143–145 of my Skates Made of Bone).Many people immigrated from Sweden to the midwestern United States in the nineteenth century. This combination of facts had led me to wonder whether Swedish immigrants to the Midwest used bone… Continue reading Did Swedish immigrants to the Midwest use bone skates?

Sven T. Kjellberg’s experiments with bone skates

Skates Made of Bone is out!

Gösta Berg

Gösta Berg (1903--1993) was a Swedish ethnologist who worked on skating, skiing, and other winter activities. His writings include three papers on bone skates, written in three different languages over a period of nearly thirty years.

How long were the races?

Skates Made of Bone

My book on bone skates is available for pre-order! You can get it directly from the publisher, McFarland, from Amazon, or from whatever bookstore you like best.

Skating party in Lödöse

The Lödöse Museum in Sweden hosts an annual skating event---on bone skates! This year, the skating is scheduled for February 11 from 1 to 3 PM; the details are here (in Swedish). Skating on bones in Lödöse, Sweden. Photograph courtesy of Marie Schmidt, Lödöse Museum. There are videos of previous years' skating events on the… Continue reading Skating party in Lödöse