I've sorted out the various editions of Robert Jones's Treatise on Skating in a new article. As I was doing this, I discovered several new things that aren't mentioned in my edition of his book. It seemed like lots of new stuff has come online in the last few years! And now it's time to… Continue reading Editions of Robert Jones’s Treatise on Skating

Author: Bev

Internet articles about the Xinjiang skates

This is just a list of links with some comments. It's an interesting example of how a story spreads and grows despite a lack of reliable new information. Here's the press release from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences by Zhou Ye (2/27/2023, in Chinese). It focuses on the non-skate finds and has roughly the… Continue reading Internet articles about the Xinjiang skates

Ice skating was not invented in Finland

Internet, stop saying it was. The idea that ice skates made from animal bones first appeared in Finland is based on a paper published in 2008 in the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. The authors, two biomechanics researchers from Manchester Metropolitan University, measured the metabolic cost of skating as compared with walking, then ran… Continue reading Ice skating was not invented in Finland

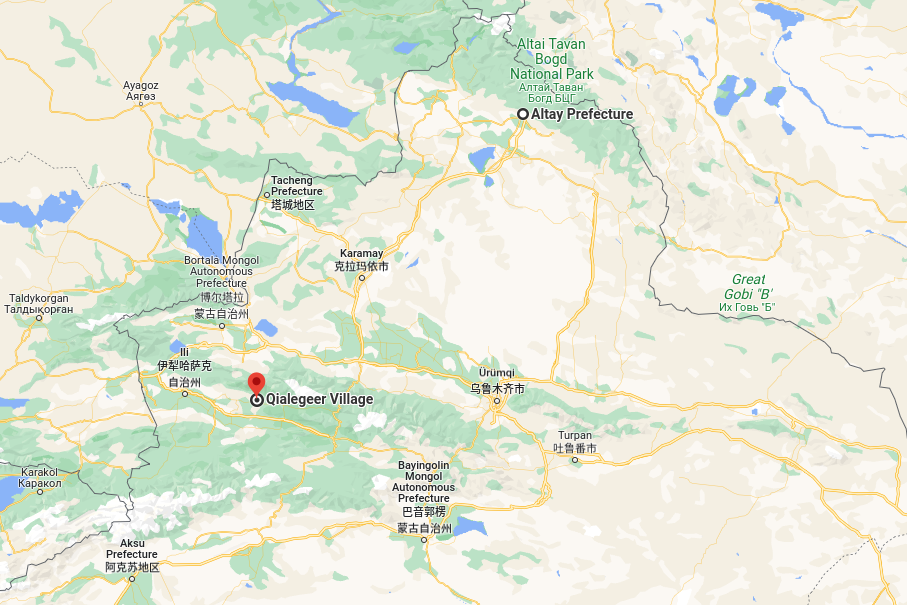

Old bone skates found in China

This last week, the news has been full of reports on the recent announcement (in Chinese) that bone skates have been found in the Xinjiang area. The skates were reportedly found at a tomb in the Gaotai Ruins, which are part of the Jiren Taigoukou Ruins in Qialege'e, a village in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous… Continue reading Old bone skates found in China

Bone skates in Fríssbók

Fríssbók or Codex Frisianus is an Icelandic manuscript written in the first quarter of the fourteenth century. It includes a copy of Magnússona saga (called Saga Sigurðar, Eysteins ok Ólafs in C. R. Unger's edition). The whole manuscript has been digitized and is available at handrit.is! Here is the part about skating, with the phrase… Continue reading Bone skates in Fríssbók

Skating on my snavelschaatsen

For the last couple of weeks, I've been learning to skate on my snavelschaatsen (long-toed skates modeled after Hieronymus Bosch skates). https://youtu.be/CJ1lPKDSakM They are very slick and work best on soft ice. It was hard to get them to stay in place, but using two laces—one to keep them attached and the other to keep… Continue reading Skating on my snavelschaatsen

Bone skates in the Guildhall Museum

The Catalogue of the Collection of London Antiquities in the Guildhall Museum lists 16 bone skates. The first, #134, is "said to have been found with two Roman sandals" at London Wall. A few of these skates, including #134, were drawn by Charles H. Whymper; his drawing is preserved in the British Museum. "Five skates… Continue reading Bone skates in the Guildhall Museum

Stevens’ Bibliography of Figure Skating

Ryan Stevens, who writes the Skate Guard blog, has taken on the gargantuan task of making sense of all the books on figure skating published in the last century and a quarter by continuing F. W. Foster’s 1898 Bibliography of Skating. It's a job worth doing and Stevens is to be commended for taking it… Continue reading Stevens’ Bibliography of Figure Skating

Vieth, On Skating

I have completed my translation of the first German book on skating, Gerhard Ulrich Anton Vieth's Ueber das Schrittschuhlaufen. It was originally a lecture given in Dessau in 1788, then published as a journal article in 1789, and finally published in book form with some additions by an anonymous editor in 1790. Vieth's book is… Continue reading Vieth, On Skating

Lunn’s Letters to Young Winter Sportsmen

The cover of the Home Farm Books reprint. Note the misused comma! Young men planning to spend the winter at an Alpine resort (which lots of rich English people did back in the day) and get involved in winter sports while there are the intended audience of this book, which was published in 1927. The… Continue reading Lunn’s Letters to Young Winter Sportsmen