Lincoln Castle Revealed from Oxbow Oxbow's new book about Lincoln Castle, Lincoln Castle Revealed: The Story of a Norman Powerhouse and its Anglo-Saxon Precursor describes two bone skate fragments found during the excavation. The authors date them to before the Norman Conquest and include them in the catalog of artifacts under "Recreation"—where they are the… Continue reading The bone skates from Lincoln Castle

Author: Bev

Robert Jones’s skates again

My Robert Jones skates. In A Treatise on Skating—the first book on skating, published exactly 250 years ago—Robert Jones describes, in great detail, his ideal skates. I made a pair and tried them out. Jones's skates are the type used in England at his time, in contrast to the Dutch type. They have short, curved… Continue reading Robert Jones’s skates again

The oldest skating art (again)

The dates of the Hieronymus Bosch paintings in my previous post aren't quite clear—there's a range of 10–20 years for each. I found it interesting that the early ends of these ranges are actually earlier than the woodcut of St. Lydwina's accident, which often gets the credit for being "[t]he first depiction of ice skating… Continue reading The oldest skating art (again)

Skating in the art of Hieronymus Bosch

I've found two instances of skating in Hieronymus Bosch's paintings. Note that they are all using snavelschaatsen! The Garden of Earthly Delights This triptych was probably painted between 1495 and 1505. Skating appears in the panel representing Hell. Courtesy of Wikimedia commons. The Temptation of Saint Anthony There's a messenger bird skating in the lower… Continue reading Skating in the art of Hieronymus Bosch

My new snavelschaatsen

Yesterday I put the finishing touches on my snavelschaatsen. I started them back around the end of February or the beginning of March, so it took me about 9 months to make them, start to finish. My finished snavelschaatsen. These skates are based on a couple of Hieronymus Bosch paintings and some archaeological finds. The… Continue reading My new snavelschaatsen

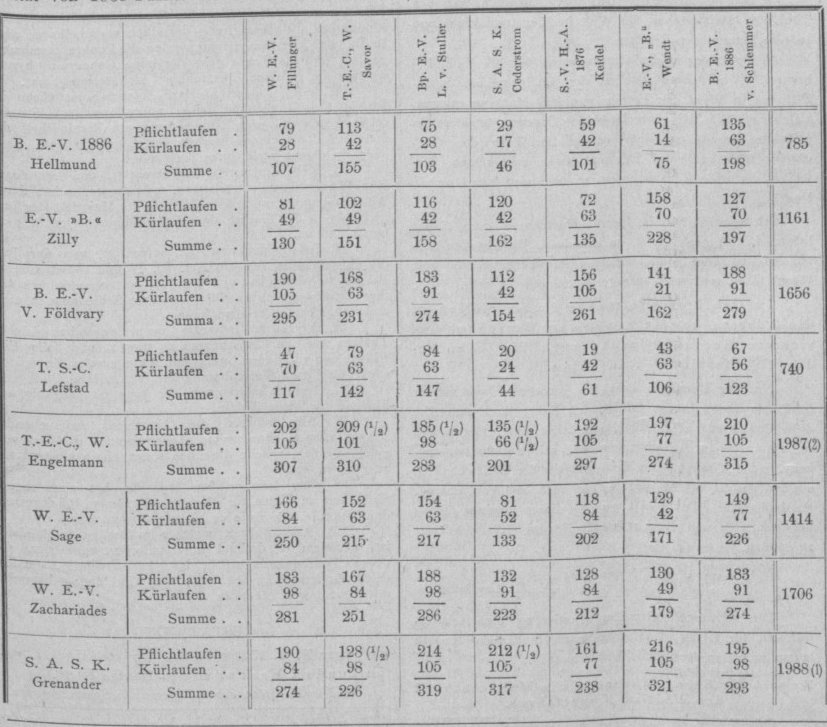

The 1893 European championship

The International Skating Union (ISU) was founded in 1892 and held its first official competition in 1893—the European championship in Berlin. The speed skating events went well. The figure skating event began the tradition of judging controversies. The problem was figuring out whether Eduard Engelmann or Henning Grenander won. Engelmann had won the previous year,… Continue reading The 1893 European championship

Goose poop in the smithy

In the first printed book on metallurgy, the Pirotechnia, Vannoccio Biringuccio describes a process for purifying iron used "outside Christendom": They say that the file it, knead it with a certain meal, make little cakes of it, and feed these to geese. They collect the dung of these geese when they wish, shrink it with… Continue reading Goose poop in the smithy

New publications

I haven't been writing much here lately, but some new things are up on Schaatshistorie.nl: Two videos from my new Evolution of Skating series: Bone skates and Archetype skates. Those links are to the English versions, they are also in Dutch here and there."Whither bone skates research?", a short article summarizing the state of research… Continue reading New publications

Fluted skates

Early skating authors had a lot of bad things to say about deep hollows on ice skates. I have said nothing of those skates whose surfaces are grooved, and are commonly called fluted skates, because I think their construction is so bad, that they are not fit to be used; in fact, they are so… Continue reading Fluted skates

English skating and national identity

My article on English skating just came out! Here's the citation: Thurber, B.A. 2021. "The English Style: Figure Skating, Gender, and National Identity." Sport History Review. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1123/shr.2020-0023. Abstract During the second half of the nineteenth century, a unique style of figure skating developed in Great Britain. This style emphasized long, flowing glides… Continue reading English skating and national identity