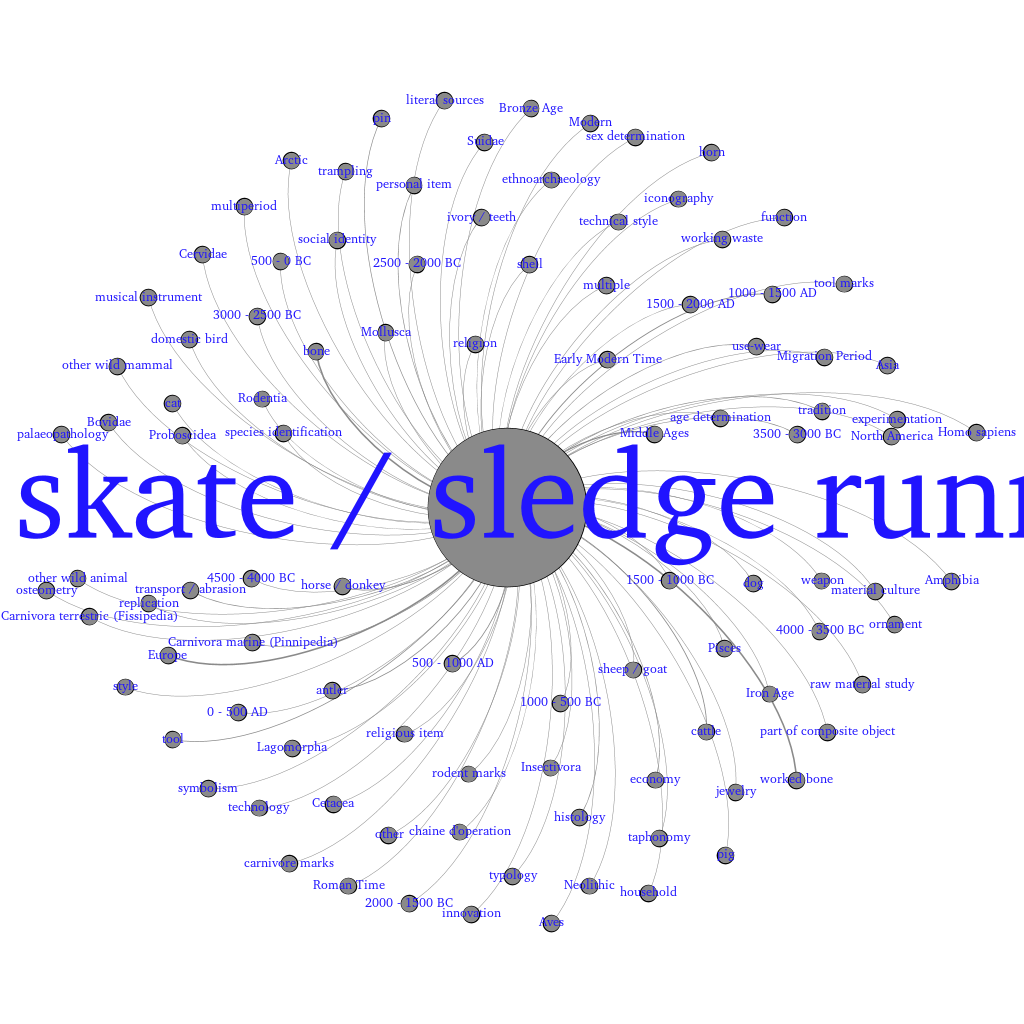

I used Gephi to make a graph of all the keywords connected to bone skates in the WBRG reference database. Graph generated using Gephi. Most of the results aren't very surprising. Of course bone skates are strongly linked to worked bone, bone, Europe, and the Middle Ages (1000–1500). More surprising are the links to North… Continue reading Bone skates and keywords

Author: Bev

Bones at a Crossroads

Arthur MacGregor

Arthur MacGregor is one of the heroes of bone skates studies. He proved that bone skates really were skates in 1975 by making a couple of pairs and skating on them. The next year, he published a really great review article. His dissertation Skeletal Materials presented the bigger picture. And then his book Bone, Antler,… Continue reading Arthur MacGregor

Leif Erikson in St. Paul

Last week I visited the statue of Leif Erikson in St. Paul, MN. Leif is known for discovering North America around 1000 CE. His exploits are described in Grœnlendinga saga (The Saga of the Greenlanders) and Eiriks saga rauða (The Saga of Erik the Red). The Leif Erikson statue in St. Paul. I was interested… Continue reading Leif Erikson in St. Paul

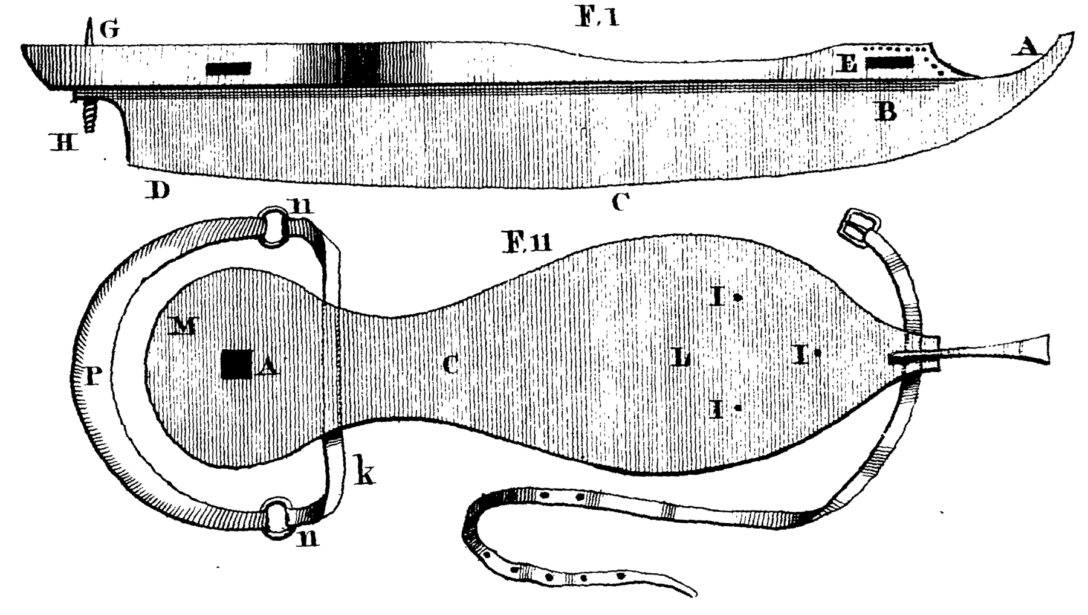

Robert Jones’s skates

In his 1772 Treatise on Skating, Robert Jones describes what he considers the ideal skate in detail, including measurements: Figure 1 (top) represents a skate, made after the English fashion, with some improvements; the proportions are as follows: Let the distance from the point of the fender, A, to the toe hook, which is shewn… Continue reading Robert Jones’s skates

1991: Skating Odyssey

In 1972, Irwin J. Polk published an article in Skating, the USFSA's official magazine, predicting what skating competitions would be like in 1991. It describes a skater doing figures with lights affixed to her skates and an overhead camera recording every move. The figures are scored by a computer based on the video. Skaters with… Continue reading 1991: Skating Odyssey

Did snow skates work?

As far as I can tell, the answer is no. The snow skates I'm thinking of have metal blades an inch wide or a bit more. They're about as long as the skater's foot and tie on to the shoes. A good example is the one I found in an antique shop. In that post,… Continue reading Did snow skates work?

Did Swedish immigrants to the Midwest use bone skates?

Two facts are clear: People were still using bone skates in Sweden in the nineteenth century (see pp. 143–145 of my Skates Made of Bone).Many people immigrated from Sweden to the midwestern United States in the nineteenth century. This combination of facts had led me to wonder whether Swedish immigrants to the Midwest used bone… Continue reading Did Swedish immigrants to the Midwest use bone skates?

The Paulsen brothers

Axel Paulsen made history in 1882, when he performed the jump that bears his name at a competition in Vienna. What's less well known is that his brother was also there. In fact, they skated together. Demeter Diamantidi wrote a nice article previewing the competitors for the Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung. It was published the day before… Continue reading The Paulsen brothers

Kemp’s bicycle skates

On January 1, 1876, the Sporting Gazette ran a notice about a new type of skate invented by one Mr. Kemp. These skates, which he called "bicycle skates," featured a large front wheel and a small rear wheel. They seem to have been intended for skating on roads normally traversed by bicycles. "The Bicycle Skate,"… Continue reading Kemp’s bicycle skates