Frank Gillett, The Graphic, March 7, 1908, 325. Image copyright the British Library Board, courtesy of the British Newspaper Archive. Dorothy Greenhough-Smith's Wikipedia page notes that "[s]he never competed at the European Figure Skating Championship because the ladies event was not added to the program until 1930." That's true as far as it goes—Hines's list… Continue reading Women in the European Championships

Author: Bev

Baseball before We Knew It

Baseball before We Knew It by David Block, 2005. I just read David Block's Baseball before We Knew It. As might be inferred from its title, this book is not about skating. It's still great. I found a lot of parallels to my work on skating history in it. It covers some of the same… Continue reading Baseball before We Knew It

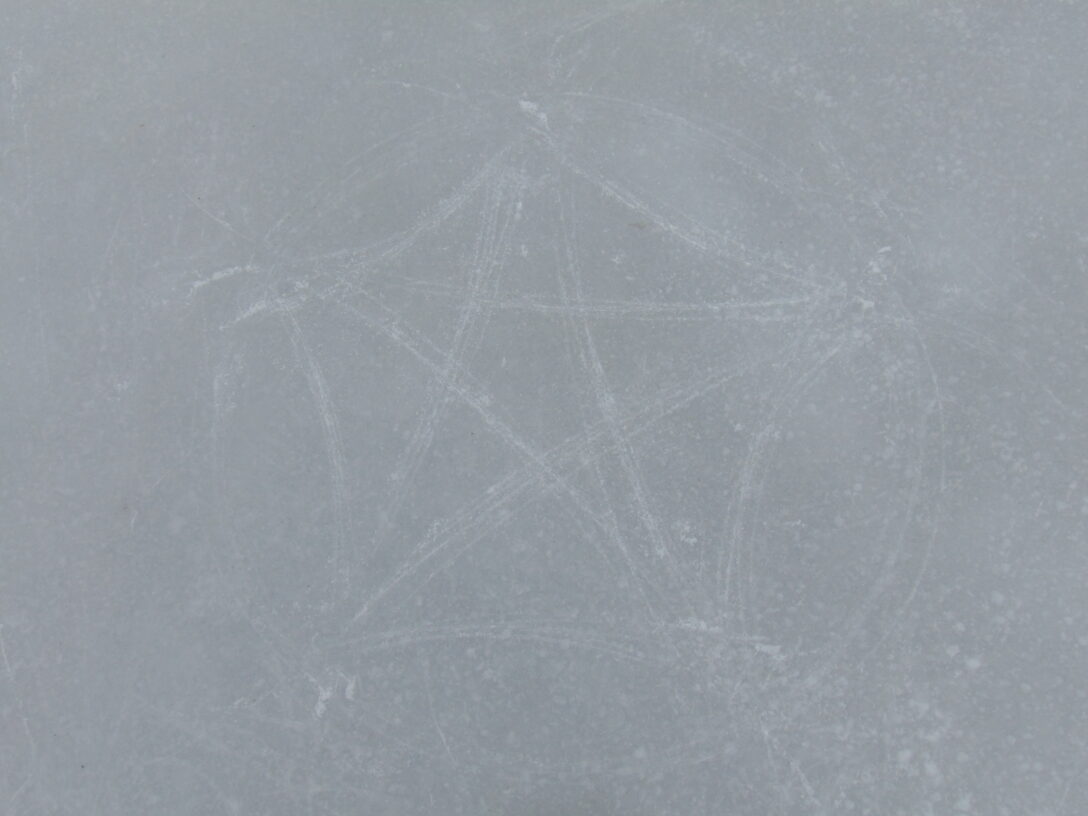

The Curtis star

The Curtis star, retraced a few times. The Curtis star was a specialty of Callie Curtis, American champion from 1969 to 1874. Instructions for skating it are given in The Skaters Text-Book (with a diagram that seems backwards to me). In the third edition of A System of Figure Skating, Vandervell and Witham quote the… Continue reading The Curtis star

The myth of skating history

My new article, "The myth of skating history: Building elitism into a sport" has been published in a special issue of Leisure Sciences on myths and mythmaking. It's about the development of figure skating's origin story—that story about medieval Scandinavians traveling and hunting on bone skates that's at the beginning of pretty much every book… Continue reading The myth of skating history

H. E. Vandervell’s hypocycloid challenge

Henry Eugene Vandervell ends The Figure Skate with a challenge: to skate a hypocycloid. The hypocycloid is the most difficult of three curves he describes: the epicycloid, the cycloid, and the hypocycloid. All three are the designs made by a point on the edge of a circle being rolled along a line. For the epicycloid,… Continue reading H. E. Vandervell’s hypocycloid challenge

Junior and senior singles and pairs in 1906

The Figure Skating Club held competitions in single and pair skating at Prince's Skating Club on March 17 and 21, 1906. The Field reported that The inclusion of pair-skating in the club programme proved a great attraction, and a good entry was secured in both the senior and junior sections."The Figure Skating Club," The Field,… Continue reading Junior and senior singles and pairs in 1906

Mrs. Syers in the Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung

Header to the first issue available in ANNO (July 1, 1880). I recently discovered the Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung archive in ANNO: Historische österreichische Zeitungen und Zeitschriften at the Austrian National Library. Spanning 1880–1927 with a few gaps, it is a fantastic resource for skating history! (Provided you read German.) This newspaper was published in Vienna, home… Continue reading Mrs. Syers in the Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung

World Figure Championship at home

I was hoping to travel to the World Figure & Fancy Skating Championships held in Plattsburgh, NY, on 12/31/2020 and 1/1/2021, but with all the public health officials advising against travel due to the pandemic, it didn't seem like a good idea. Instead, I skated the championship at home, mostly on my backyard rink. The… Continue reading World Figure Championship at home

Football on roller skates

This image from the Illustrated London News in 1907 speaks for itself. The Illustrated London News, January 19, 1907, p. 105. Image courtesy of the British Newspaper Archive. The caption reads: Football on roller-skates was inaugurated recently for men at Brighton skating-rink, and the pastime was very soon taken up by women. The game is… Continue reading Football on roller skates

Goethe & Klopstock on ice skates

In his autobiography, Goethe recounts a conversation with his friend Klopstock about whether the German word for an ice skate should be Schlittschuh or Schrittschuh. They spoke namely in good southern German of Schlittschuhen, which he did not accept as valid because the word does not come from Schlitten, as if one puts on little… Continue reading Goethe & Klopstock on ice skates