The idea of designing your own figure is something that goes way back in figure skating. Late nineteenth-century competitions in the International style invited skaters to create their own patterns on the ice, called special figures. Many of these were published in books like Holletscheck's Kunstfertigkeit im Eislaufen. Some were actually what we'd call freestyle… Continue reading Creative figures and the USFS Adult Gold Figure test

Category: Figures

1991: Skating Odyssey

In 1972, Irwin J. Polk published an article in Skating, the USFSA's official magazine, predicting what skating competitions would be like in 1991. It describes a skater doing figures with lights affixed to her skates and an overhead camera recording every move. The figures are scored by a computer based on the video. Skaters with… Continue reading 1991: Skating Odyssey

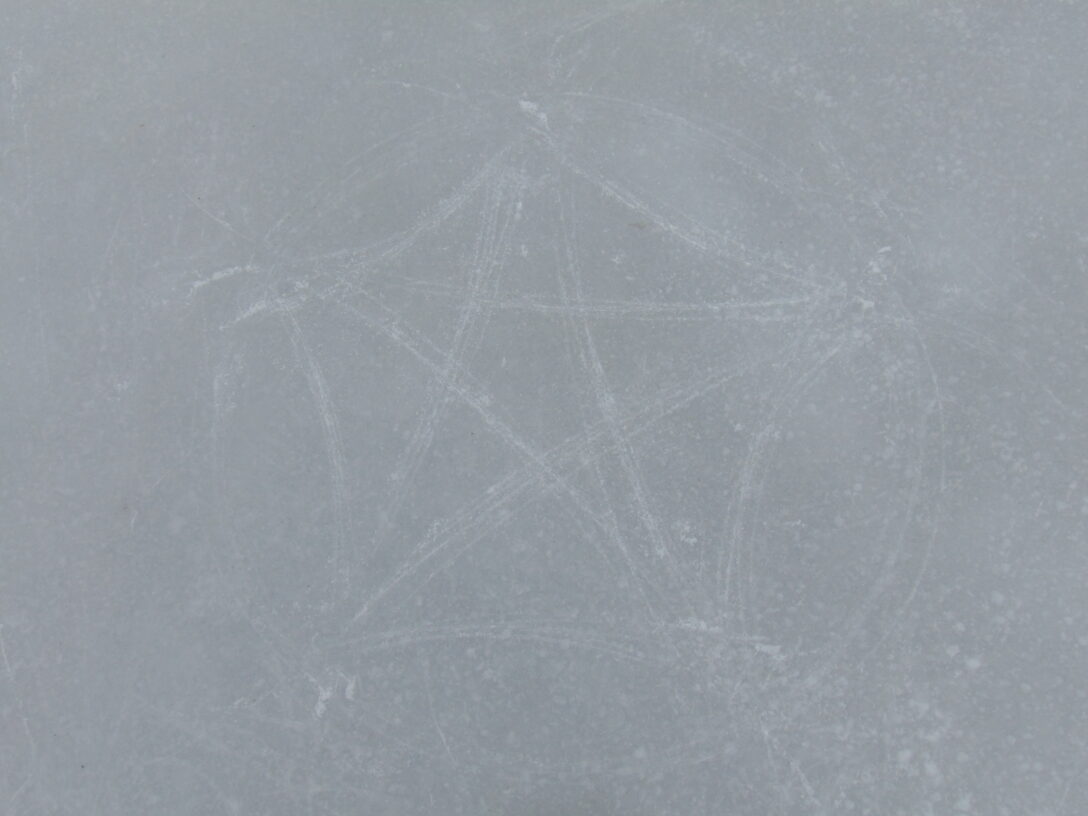

The Curtis star

The Curtis star, retraced a few times. The Curtis star was a specialty of Callie Curtis, American champion from 1969 to 1874. Instructions for skating it are given in The Skaters Text-Book (with a diagram that seems backwards to me). In the third edition of A System of Figure Skating, Vandervell and Witham quote the… Continue reading The Curtis star

H. E. Vandervell’s hypocycloid challenge

Henry Eugene Vandervell ends The Figure Skate with a challenge: to skate a hypocycloid. The hypocycloid is the most difficult of three curves he describes: the epicycloid, the cycloid, and the hypocycloid. All three are the designs made by a point on the edge of a circle being rolled along a line. For the epicycloid,… Continue reading H. E. Vandervell’s hypocycloid challenge

World Figure Championship at home

I was hoping to travel to the World Figure & Fancy Skating Championships held in Plattsburgh, NY, on 12/31/2020 and 1/1/2021, but with all the public health officials advising against travel due to the pandemic, it didn't seem like a good idea. Instead, I skated the championship at home, mostly on my backyard rink. The… Continue reading World Figure Championship at home

Timeline of the World Figure Championship

This event is now in its sixth year! To celebrate, here is a timeline. This information is drawn from the World Figure Championship website, the World Figure Sport website, the various versions of these sites archived in the Wayback Machine, and my own notes and recollections. 2015 Lake Placid, NY The competition took place on… Continue reading Timeline of the World Figure Championship

Roller skaters still do figures

Figures were once the backbone of figure skating on ice (hence the name in English), but experienced a steep decline in popularity after they were dropped as a competitive requirement in 1991. Today, ice skaters rarely do them. In roller skating, in contrast, figures continue to thrive---on quad skates. They don't really work on inlines.… Continue reading Roller skaters still do figures

Marks or tracings?

Die Marken auf dem Eise sind das unauslöschliche Sündenregister, welches die Schlittschuhseele des Eisläufers, sein Schwerpunkt, auf dem Gewissen hat.

Loop skates

Back when all competitive skaters did both figures and freestyle, everyone who had reached a certain level had two pairs of skates, "patch skates" for figures and freestyle skates. Dick Button had a third pair just for loops.

Creative figures

Creative figures are getting popular because they're in the World Figure Championship. These patterns of tracings designed by skaters are nothing new.